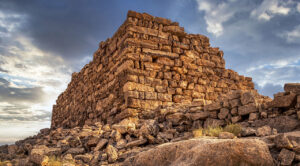

The great basalt fort of Deir Al-Kahf is located on the north side of the …

One of my favorite places to visit in Eastern Jordan, Qasr Usaykhim seats …

The small military Roman Fort of Uweinid lies on the tip of a law basalt spur …

Qasr Bshir (Castra Praetorii Mobeni), one of the best-preserved Roman forts …

Qasr Abu el-Kharaq is a watchtower that originally belonged to the defense …

Qasr el-Al, one of three Nabatean / Roman fortifications within the visual contact …

Jordan’s Roman Forts

GUIDE TO The Limes Arabicus – The Desert Frontier of the Roman Empire

The annexation of the Nabataean Kingdom in A.D. 106 by Roman Emperor Trajan marked a significant expansion of the Roman Empire, adding Arabia as a new province. Stretching across modern-day Jordan, the Sinai, and southern Syria, this newly acquired region required fortified defences. The Romans, following their well-established strategy for border control, developed the Limes Arabicus—a network of forts, camps, and watchtowers interconnected by a system of roads.

At its height, the Limes Arabicus extended for about 1,500 kilometres, from Bosra in southern Syria to Aqaba (ancient Aila) on the Red Sea’s arm. Notable fortifications included Qasr Bshir, Qasr Thuraia, Qasr Al-Hallabat, and the significant legionary camps at El-Lejjun and Udhruh near Petra. Despite its military focus, this extensive frontier system also safeguarded trade caravans travelling from the Arabian Peninsula, securing both economic stability and the safety of Roman officials.

Adjacent to these fortifications, Trajan orchestrated the construction of the Via Nova Traiana, a pivotal highway connecting Bosra to Aqaba. Spanning 430 kilometres and completed between 111 and 114 A.D., this road epitomised Roman engineering excellence. It facilitated troop mobility, administrative efficiency, and the protection of high-value trade routes.

The Late Roman period (135–324 A.D.) witnessed further enhancements to the Limes Arabicus. Many Nabataean forts were rebuilt or expanded, while newer constructions, such as Qasr Uweinid and Khirbet el Fityan, were strategically added. This era also saw the development of the immense military camps at El-Lejjun and Udhruh, underscoring the region’s growing military importance for deterring external threats.

However, by the late 5th century, Roman forces gradually withdrew. Their role along the frontier was assumed by native Arab foederati, predominantly the Ghassanids, who acted as auxiliaries. With the rise of Muslim Arab forces and their eventual conquest, the Limes Arabicus fell into decline. While some fortifications were reused and reinforced during subsequent centuries, the system largely faded into history.

For over 500 years, the Limes Arabicus effectively defended the region, fostering stability during the Pax Romana. It facilitated developments in trade, the spread of early Christianity, and dense settlement across Transjordan, a level of habitation not seen again until modern times. These remarkable structures stand as a testament to Roman ingenuity and legacy. Preserving them today is not only essential for safeguarding history but also for sharing their story with future generations.

During the Early Roman period (63 B.C.–A.D. 135), Transjordan was an integral part of the Nabataean Kingdom. To safeguard their borders, settlements, and vital caravan routes, the Nabataeans devised a network of small forts and watchtowers. These structures were often newly built or constructed atop the remains of Iron Age fortifications.

When the Romans annexed the Nabataean state in A.D. 106, these defensive positions were seamlessly integrated into the emerging limes system—Rome’s intricate frontier defence network. The Nabataean fortifications effectively formed the foundational framework of what became known as the Limes Arabicus. While identifying this transition is more challenging in the northern areas of Transjordan due to the lack of Nabataean pottery, evidence from sites like Deir El-Kahf and Qasr Al-Hallabat, which feature Early Roman pottery, hints at earlier Nabataean military occupation.

Not content with just utilising existing structures, the Romans began expanding and establishing new ones as well. For instance, they constructed Qasr El-Kithara in the southernmost regions during the annexation. Significant effort was also directed at developing a key north-south road, the Via Nova Traiana, which connected the provincial capital of Bostra to Aqaba (Aila). By A.D. 111, this vital road was complete, enhancing mobility and connectivity across the province.

The Late Roman period (A.D. 135–284) witnessed a marked increase in the number of fortifications. Many Nabataean forts were either expanded or reconstructed, and prominent new installations like Dajanya, Al-Hallabat, and Qasr Usaykhim sprang up. Rather than focusing on a particular area, the Romans ensured the entire frontier received attention, reflecting the importance of maintaining stability across this volatile region. While much of the second century was defined by peace under Roman rule, the third century brought instability in the form of civil wars, invasions, and the meteoric rise of Palmyra. Palmyrene dominance, which extended as far as Egypt, severely disrupted Roman efforts in Arabia and beyond.

With the fall of Palmyra under Emperor Aurelian (A.D. 270–275), the Romans embarked on a period of reconstruction. Emperor Diocletian (A.D. 284–324) led these efforts with a particular focus on fortifying the empire’s northwestern regions. During this time, strategic forts like Qasr Azraq, Qasr Uweinid, and Qasr Usaykhim formed a defensive line to control movement from the Sirhan area. Meanwhile, the construction of key forts like Zona, Qasr Thuraia, Qasr Bshir, and Khirbet el Fityan strengthened the central sector of the Limes Arabicus. Of particular importance were the two massive camps at El-Lejjun and Udhruh, near the iconic city of Petra. These installations underscored the Romans’ commitment to securing the region during this tumultuous period.

By the 4th century, the Roman frontier remained robust, but it began to decline during the Early Byzantine period (A.D. 392–450). By the end of the 5th century, most forts in Arabia were abandoned, marking a gradual cessation of direct Roman military presence. This withdrawal may, in part, be attributed to the Byzantine Empire’s reliance on the Ghassanids, local vassals trusted to manage and defend the region in their stead.

Together, these fortifications tell a story of resilience, adaptation, and the enduring strategic importance of Transjordan. From the Nabataean Kingdom to the Roman Empire and beyond, the region stood as a vital juncture between civilisations, guarded by an evolving network of forts and frontier lines that shaped its history.